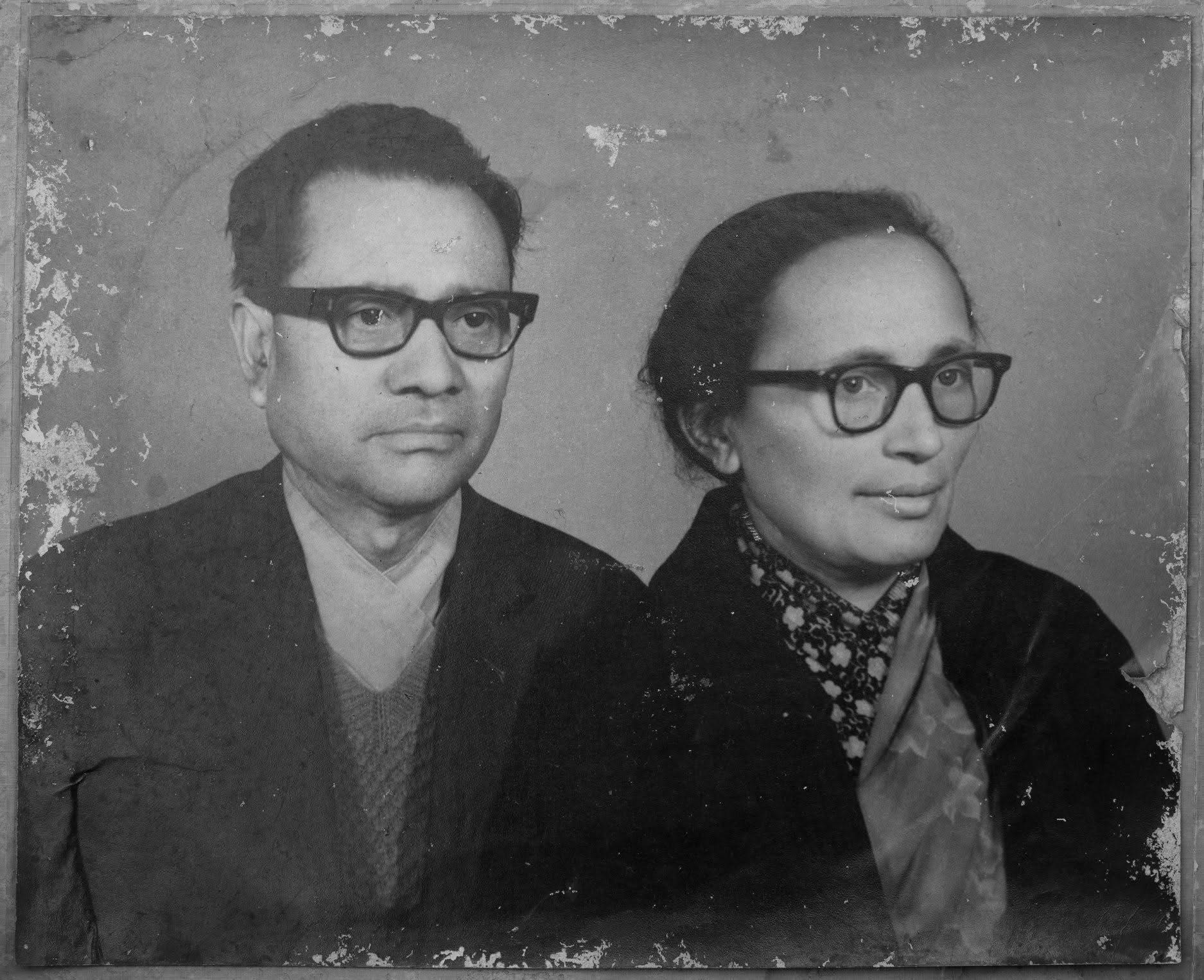

Heera Devi Yami was not a woman who sought the spotlight. Yet, in the shadows of an authoritarian era in Nepal, her quiet courage became a beacon for her community. Born in the early 20th century, she defied social norms to teach children in secret, faced imprisonment even with her infant at her side, and sustained a household and a movement with equal determination. This book is an attempt to capture her voice — through the memories of those who loved her most — and to place her life in the long sweep of Nepal’s struggle for freedom and dignity.

Chapter One

Listening to Silence

Heera Devi Yami did not leave behind memoirs. She did not write speeches or claim recognition for the work she did. What she left instead were memories—held by her children, her neighbors, and those who lived alongside her in a time when courage had to remain quiet. This book begins by listening to that silence.

To understand Heera Devi Yami’s life, one must first understand the world into which she was born. Nepal in the early twentieth century was ruled by the Rana regime, a hereditary autocracy that controlled not only politics but also education, movement, and speech. Education for women was discouraged, sometimes forbidden. Political dissent was punished with imprisonment, exile, or worse. In this environment, even ordinary acts—teaching a child, sheltering a visitor, speaking freely—could become acts of resistance.

Heera Devi Yami’s resistance was loud. Her arrest speaks.

Those who remember her do not begin by calling her a political activist. They remember her as a woman who worked constantly. . She was a mother, a caretaker, a teacher, and a quiet organizer of reforming political system. Her life unfolded at the intersection of domestic responsibility and political struggle, a place where history often forgets to look.

Family community members recall that she believed deeply in education. Not education as privilege, but education as survival. In a society where women were expected to remain confined to household roles and critical thinking and questioning used to be against social norms, she understood learning as a form of freedom. Teaching children— secretly—because education used to be banned during her days was not only an act of care but an act of defiance. To educate was to imagine a future beyond fear.

Oral accounts describe how she taught despite risk. Despite surveillance. Despite the knowledge that discovery could bring arrest. These memories are not always precise about dates or locations, but they are precise about feeling: the tension of secrecy, the fear of informers, the discipline required to live cautiously while remaining committed to one’s values.

One recurring memory shared by those who knew her is her ability to endure hardship without complaint. Even during times of extreme scarcity, she insisted on sharing whatever little the family had. This was not romantic idealism; it was a principle she lived by. The belief that dignity could be preserved even when material conditions were harsh shaped her household and those around her.

Her personal life cannot be separated from the political context of the time. Her husband spent much of his life in and out of prison for his political activities. This reality placed an extraordinary burden on Heera Devi Yami. While others were imprisoned, she sustained the family. While others were forced underground, she provided shelter. While others spoke publicly, she ensured that life continued—food was prepared, children were cared for, and visitors were protected.

Oral testimonies describe her home as a place of quiet solidarity. Activists passed through. Families of imprisoned comrades were supported. No records were kept. No credit was taken. What mattered was that people survived. There are published records of underground activists of those days on Heera Devi Yami.

One of the most striking moments recalled by family members is her arrest while caring for a very young child. The news was censored in Nepal. The news about her arrest with breast feeding child was published in several newspapers of India. Even in detention, she remained a caretaker—both for her infant and for others around her. These accounts do not dramatize her suffering. Instead, they emphasize her steadiness. She endured not by resisting loudly, but by refusing to break.

In oral history, repetition matters. When multiple voices return to the same qualities—steadfastness, generosity, discipline—we begin to understand character rather than event. Heera Devi Yami’s life was not defined by a single heroic moment, but by sustained moral consistency across decades of uncertainty.

This chapter does not seek to prove her importance through official records or public recognition. It seeks to establish something more fragile and more powerful: presence. She was there—when education was denied, when families were broken by imprisonment, when fear was routine. She remained.

The chapters that follow will draw more deeply from spoken memories: stories told by her children, reflections shaped by distance and time, fragments preserved in conversation rather than archives. Together, these voices form a history that is personal, political, and necessary.

This book begins not with a proclamation, but with listening. Because some lives change history not by announcing themselves, but by holding firm when history presses hardest.

Chapter Two

Childhood and Early Influences

Writing about the childhood of Heera Devi Yami requires listening more carefully than reading. There are few formal records of her early life. What survives instead are memories—passed from one generation to another—and the values that remained consistent throughout her life. These memories do not always provide dates or precise details, but they offer something equally important: insight into how her character was formed.

Heera Devi Yami was born into a society shaped by tradition, hierarchy, and strict social expectations, especially for women. From an early age, girls were prepared for lives centered on the household. Education was limited, opportunity narrower still. Silence and endurance were often presented as virtues. Growing up in this environment, she learned early how much discipline daily life required.

Family recollections describe her as observant and responsible even as a young girl. She noticed how work was divided, how authority operated, and how hardship was absorbed quietly by women around her. These observations did not immediately translate into rebellion. Instead, they nurtured patience, self-control, and an ability to read situations carefully—qualities that later became essential to her survival and resistance.

There is no evidence that her childhood was overtly political. Yet, the foundations of her political consciousness were being laid in ordinary experiences. Inequality was not something she learned from books; it was something she saw. The contrast between privilege and deprivation, between those who spoke freely and those who lived cautiously, left a lasting impression on her understanding of justice.

Her access to formal education was considered crime and dangerous, but her desire to learn was not. Whatever opportunities she encountered—however small—were treated seriously. This early deprivation may explain her lifelong commitment to education, particularly for children and women. Teaching later became not just a practical activity for her, but a moral responsibility shaped by what she herself had been denied.

One of the most important influences of her childhood was the normalization of responsibility. From a young age, she understood that individual comfort was secondary to collective well-being. Helping at home, caring for others, and managing scarcity were not exceptional acts; they were everyday realities. These early lessons prepared her for a life in which sacrifice would not be episodic, but continuous.

The social expectations placed on women did not disappear from her life; instead, she learned how to work within them. Domestic labor became a form of strength rather than confinement. Silence became strategic rather than submissive. Endurance became purposeful. Rather than rejecting her assigned roles, she reshaped them into tools for survival and support.

Oral accounts emphasize her ability to learn by watching others. She absorbed lessons from Jagat Lal master of Masan Galli Keltole of Kathmandu valley who was engaged in educating children secretly and from the unspoken rules governing public and private life. This habit of observation later allowed her to assess risk accurately—to know when to act and when to wait. It was a skill rooted not in ideology, but in lived experience.

The hardships of her early years also fostered emotional resilience. Scarcity, uncertainty, and social restriction did not weaken her resolve; they strengthened her capacity to endure without bitterness. This emotional steadiness would later define how she faced imprisonment, separation, and constant threat.

By the time political struggle entered her life directly, it did not arrive as a sudden transformation. It was the natural extension of values formed in childhood: responsibility toward others, belief in education, and acceptance of personal hardship for collective good. What appeared later as courage had been rehearsed quietly for years.

This chapter does not attempt to romanticize her childhood. It was not extraordinary in circumstance. What was extraordinary was how she absorbed those circumstances—how ordinary experiences produced uncommon steadiness. Her early life shows us that resistance does not always begin with slogans or movements. Sometimes it begins with attention, discipline, and care.

In the next chapter, we turn to the period when these early influences took visible shape—when marriage, family life, and political struggle began to intersect, and when the private world she had learned to manage became inseparable from public resistance.

Chapter Three

Marriage, Family, and the Awakening of Political Commitment

Marriage marked a turning point in Heera Devi Yami’s life—not because it reduced her world, but because it expanded the responsibilities she already carried. Entering married life did not remove her from the political currents of the time; instead, it placed her at their center, where the personal and the political became inseparable.

She married into a household deeply affected by political struggle. Her husband’s involvement in the movement against the Rana regime meant that imprisonment, surveillance, and uncertainty were not distant possibilities but everyday realities. For Heera Devi Yami, political commitment was not first encountered as ideology or organized activity; it arrived through lived experience—through absence, fear, and the constant need to adapt.

Family memories recall that she entered marriage with clear understanding. She knew that her husband’s political path would bring hardship, yet she accepted it without illusion. One family member later reflected that she believed a person who could dedicate himself to a collective cause would also be capable of moral integrity in personal life. This belief shaped her acceptance of a life defined not by stability, but by purpose.

As children were born, her responsibilities multiplied. She raised a large family under conditions that were often precarious—financially, emotionally, and politically. Yet oral accounts emphasize that the household never functioned in isolation. The home became a living space for movement, solidarity, and quiet organization. Activists passed through. Messages were relayed. Families of imprisoned comrades were supported. Domestic life and political struggle flowed into one another without clear boundary.

In this context, Heera Devi Yami’s political consciousness deepened. It did not express itself through public speeches or visible leadership, but through sustained action. She ensured that children were fed and educated even when resources were scarce. She protected visitors without asking questions that might endanger them. She absorbed anxiety so that others could function. These acts, repeated over years, constituted a form of political labor that rarely appears in official histories.

Her husband’s repeated imprisonment intensified her role as both parent and anchor. With one partner removed from the household for long periods, she became the sole manager of family life. Oral testimonies describe her days as carefully structured—balancing childcare, household work, and the demands of supporting a political network. There was little room for hesitation. Decisions had to be made quickly and quietly.

One of the most striking moments remembered by community members is her arrest while caring for a very young child. Detention did not exempt her from motherhood; nor did motherhood protect her from punishment. Even in confinement, she continued to care for her child and for others around her. This experience did not radicalize her suddenly; rather, it affirmed a commitment that had already taken shape through years of endurance.

The Rana authorities went to extreme lengths to break her resolve. In their desperation to extract internal details of revolutionary activities, they threatened to kill two of her infant children, using terror as a tool of interrogation. This calculated cruelty was intended to shatter her mental strength and force compliance. Yet, despite this profound psychological torture and the unbearable fear inflicted upon a mother, Heera Devi Yami did not betray the underground movement. Her endurance under such threats stands as one of the most harrowing examples of the personal costs borne by women in Nepal’s struggle against the Rana regime. She was not a woman who could be silenced or subdued. Even when her young children were used as a means of intimidation, she did not break.

Entrusted with carrying secret information and safeguarding hideouts at the height of Rana repression, Heera Devi Yami operated at the most dangerous intersection of resistance and survival. The regime’s discovery of her role led to threats against her infant children, yet she continued her work with unwavering resolve. Through careful coordination, silence under coercion, and an extraordinary capacity for risk, she successfully fulfilled a strategic function that allowed the underground movement to endure during its darkest hours.

Under threat, she protected secret information even at great cost to her own safety. Her courage inspired both local neighbors (e.g., Chalkumari, who risked her own safety to help Heera Devi) and later activists.

At that time, the community lacked political awareness. People were effectively brainwashed to despise anyone involved in the underground movement. They would whisper, 'She is no good; she is unfit for society.

Even friends who once walked side-by-side with Heera Devi began to view her as an enemy. Because she moved secretly between safe houses and met with fellow activists under the cover of night, society branded her with the slur of a 'whore.' They treated her like a social contagion, hurling abuse and shooing her away with sounds of 'chi-chi' and 'hun-hoon'—as if she were an animal or a curse to be driven from their sight." The community was "brainwashed" to view underground activists as moral failures. Heera Devi wasn't just ignored; she was actively and vocally rejected by the very people she was likely fighting for.

The emotional cost of such a life was significant, but oral accounts emphasize her restraint rather than her suffering. She did not dramatize hardship. Instead, she normalized it. Scarcity, separation, and fear were treated as conditions to be managed, not as reasons to withdraw. This emotional discipline allowed the family to survive periods that might otherwise have broken it.

Marriage also introduced her to broader networks of political solidarity, particularly among women. Wives, mothers, and sisters of activists formed informal systems of support—sharing food, information, and care. Within these networks, Heera Devi Yami’s quiet reliability became well known. Trust was built not through rhetoric, but through consistency.

Over time, her understanding of political struggle matured. It was no longer limited to resistance against a regime, but expanded into a commitment to sustaining life under oppression. Feeding children, educating them, protecting the vulnerable, and preserving dignity became political acts in themselves. Through family life, she came to embody a form of politics rooted in care.

This chapter shows that Heera Devi Yami’s political awakening did not occur in a single moment. It unfolded gradually, shaped by marriage, motherhood, and daily responsibility. Her commitment was not declared; it was lived. It grew not from slogans, but from necessity.

In the next chapter, we turn to the period when this commitment faced its harshest tests—years of intensified repression, imprisonment, and personal sacrifice, during which her quiet strength became indispensable to both family and movement.

Chapter Four

Repression, Imprisonment, and Endurance

Repression did not arrive suddenly in Heera Devi Yami’s life. It deepened gradually, tightening its grip as political resistance intensified. Surveillance, fear, and uncertainty became enduring features of daily existence. For those already living on the margins of safety, the line between ordinary life and punishment was always thin.

By this stage, imprisonment was no longer an abstract threat. It was a recurring reality. Arrests happened without warning. Homes could be searched, movements restricted, conversations overheard. For Heera Devi Yami, repression was not experienced only through her husband’s repeated detentions, but directly through her own confinement.

In the early decades during her time very few women in Nepal had the opportunity or social permission to write critically or circulate politically charged information. Heera Devi Yami was a rare exception. During her extended stays in Calcutta and Kalimpong for the treatment of tuberculosis, she gained exposure to a wider intellectual and political world. There, she regularly read Hindi and English newspapers, which deepened her understanding of anti-colonial and democratic movements and strengthened her political awareness. This experience equipped her with the ability to write, interpret political developments, and communicate ideas effectively. Upon her return, Heera Devi Yami moved discreetly through Bhaktapur, Patan, and the core areas of Kathmandu, carrying information and messages that supported underground networks. Through these quiet yet risky efforts, she played an important role in mobilizing people and sustaining clandestine activities aimed at overthrowing the Rana regime.

Despite her fragile hearing and pregnancy, Heera Devi Yami was repeatedly subjected to severe intimidation and pressure, yet she neither abandoned her beliefs nor yielded to fear.

(2004/2005 Bikram Sambat)

Although women were deprived of voting and political rights, they participated in protests and processions. Under her leadership, organized marches were held, Heera Devi Yami took an active and responsible role in these demonstrations.

Oral accounts recall her arrest while she was caring for a very young child. This moment, remembered with particular clarity by family members, captures the cruelty of the political environment. Motherhood did not protect her from punishment, nor did imprisonment suspend her responsibilities. Detention added another layer to the labor she already carried.

In prison, she was forced into conditions designed to break both body and spirit. Food was scarce, hygiene minimal, and uncertainty constant. Yet oral testimonies emphasize not her suffering, but her composure. Even in confinement, she continued to care for others—sharing food, offering comfort, maintaining dignity in spaces meant to strip it away.

Imprisonment exposed the gendered nature of repression. Women were punished not only as political actors, but as mothers and caregivers. Separation from children was used as a weapon. Yet, rather than internalizing this punishment as personal failure, Heera Devi Yami treated it as another condition to endure. Her resilience was not dramatic; it was methodical.

Release did not mean freedom. Surveillance continued. Fear lingered. Each return home required re-establishing routines under altered conditions. Children had grown. Resources were depleted. Networks had shifted. Recovery was never complete before the next disruption arrived.

Despite this, oral histories describe her refusal to withdraw from responsibility. She resumed caring for family and supporting others without framing herself as a victim. The language used by those who remember her emphasizes steadiness rather than heroism. She endured because endurance was necessary.

Repression also reshaped the household. Children learned early about secrecy, caution, and silence. Yet they also learned about courage—not as defiance, but as persistence. Heera Devi Yami did not instruct them through speeches. She taught by example, demonstrating how to live with integrity under pressure.

Imprisonment altered her understanding of political struggle. Resistance was no longer defined solely by opposition to authority, but by the preservation of humanity within dehumanizing systems. To remain kind, disciplined, and generous under such conditions was itself a political act.

The cumulative weight of repression took a toll. Years of anxiety, deprivation, and separation left physical and emotional marks. Oral accounts do not romanticize this cost. They acknowledge exhaustion and grief. Yet they also emphasize her refusal to let hardship dictate her values.

Through repeated cycles of arrest and release, she developed a form of endurance that was both personal and communal. Her ability to withstand repression allowed others to continue their work. Her steadiness became a source of reassurance within fragile networks of resistance.

It was during one of the most precarious phases of the anti-Rana struggle that Heera Devi Yami’s strength became unmistakably visible. As confusion spread within sections of the underground network and some activists attempted to blunt or divert the momentum of the movement, she remained unwavering. Working quietly but decisively, she safeguarded lines of trust, protected the flow of information, and held together fragile links between comrades. At a time when the movement risked unraveling from within, her steadiness helped keep its purpose intact.

During one of the most dangerous periods of the Rana regime, Heera Devi Yami carried resistance not only in her actions but in her body. She moved under constant threat with her unborn child, Timila Yami, in her womb; her two-year-old son, Vidhan Ratna, strapped to her back; and her four-year-old daughter, Dharma Devi, walking beside her—hungry, exhausted, and uncertain. Fear was so pervasive that people were often too frightened even to be seen near her. Yet she continued to move, to carry messages, to survive. In those moments, courage was not abstract—it was maternal, physical, and relentless.

Doors stayed closed. Gates did not open. The fear of torture by the Rana regime’s secret services was so deep that people dared not be seen helping her. Even at the homes of relatives and friends, she was turned away—met not with refuge, but with rebuke born of terror.

This chapter does not present imprisonment as a turning point marked by dramatic transformation. Instead, it shows how repression clarified what had already been formed: a commitment to care, discipline, and collective survival. Endurance was not passive acceptance; it was an active choice, made repeatedly under constraint.

In the next chapter, we turn to the later years of Heera Devi Yami’s life—when political change arrived unevenly, and when the long effects of repression shaped memory, health, and legacy.

Chapter Five

Later Years, Memory, and Legacy

The later years of Heera Devi Yami’s life unfolded in a quieter political landscape, but not in a quieter emotional one. Political change did not arrive all at once, nor did it erase the long effects of repression. What followed was not relief, but adjustment—learning how to live after years defined by vigilance, loss, and endurance.

With the gradual transformation of Nepal’s political environment, some of the dangers that had shaped her earlier life receded. Yet the habits formed under repression remained. Caution, restraint, and discipline continued to guide her daily life. Oral accounts describe her as steady and composed always very confident enriched with learning lesions with hardships of political life. and never presenting herself as central to history.

Health concerns became more visible in these years. The cumulative strain of imprisonment, scarcity, and prolonged anxiety of her challenging nature during riskiest periods of Rana regime left their mark. Family members recall periods of physical weakness and fatigue during critical times of starvation and illness. Yet even as her body slowed, her sense of responsibility did not diminish. Care continued to flow outward—to communities who sought her guidance.

Memory played a complex role in her later life. She remembered events clearly, but chose her silences carefully. Hardship experiences were shared repeatedly. Painful memories were not hidden out of shame, but out of a desire to shield others from their weight.

Within communities her role gradually shifted from provider to moral anchor. Younger generations learned not through formal instruction, but through presence. Her values—education, fairness, restraint, and generosity—were transmitted through everyday interaction. Stories about her life were told not as legends, but as lessons embedded in ordinary conversation.

Oral histories emphasize that she never claimed authorship of political change. She did not frame her sacrifices as exceptional. When acknowledged, she often redirected attention to others or to collective struggle.

Her legacy is therefore found in published documents or public recognition. Children educated despite adversity. Families sustained during crisis. Ethical standards maintained when compromise would have been easier. These outcomes, while difficult to measure, form the substance of her historical contribution.

In death, as in life, she was remembered communities poured tears and shared her sufferings. Memory circulated through conversations, through stories told at home, through the lives shaped by her presence. Over time, these memories accumulated, revealing patterns of care and resilience that demanded recognition.

The act of recording her life through oral history is itself part of her legacy. It acknowledges forms of political labor that are often excluded from official narratives—labor rooted in care, endurance, and moral consistency. Her story challenges narrow definitions of activism and leadership, insisting that history is also made in kitchens, courtyards, and prison cells.

Heera Devi Yami’s life reminds us that political change is sustained not only by visible leaders, but by those who hold communities together under pressure. Her endurance made continuity possible. Her care preserved dignity. Her silence, when chosen, protected others.

This book seeks to listen—to preserve the voices that remember her, and to situate her life within a broader history that often overlooks women like her. In doing so, it affirms that legacy is not only what is declared, but what endures.

Conclusion

Listening to Quiet Lives

This book began with listening.

It begin with archives, proclamations, or official histories, including fragments of memory—stories told at community gatherings, recollections shared across generations, and words preserved in conversations and social media posts. Through these voices, the life of Heera Devi Yami emerges not as a spectacle of political leadership, but as a testament to endurance, care, and moral consistency under extraordinary pressure.

Her life challenges conventional ways of understanding history. Political history often privileges visibility: speeches, titles, victories, and public recognition. Yet Heera Devi Yami’s contribution unfolded largely outside such frames. Her labor was continuous rather than episodic, quiet rather than declarative, relational rather than institutional. It was carried out in households and communities disrupted by repression, in years marked by fear and scarcity, and in the emotional work of sustaining others while enduring her own losses.

Oral history allows us to recognize this kind of labor as historical. By centering lived experience, it expands what counts as political action. It shows how resistance can take the form of survival, how courage can be expressed through care, and how dignity can be preserved without visibility. In listening to women like Heera Devi Yami, we hear histories that were never meant to be forgotten, but were never designed to be recorded.

This book does not claim to offer a complete account of her life. Memory is partial, and oral history is shaped by what is remembered, what is spoken, and what remains silent. Those silences are not gaps to be filled, but realities to be respected. They remind us that not all pain seeks articulation, and not all truth demands exposure.

What emerges instead is a portrait shaped by relationships: a woman as daughter, wife, mother, comrade, and moral presence. Her political awakening was inseparable from her family life; her endurance inseparable from collective struggle. She did not separate the personal from the political because her circumstances never allowed such a division.

In recording her story, this book also reflects on the responsibility of remembering. Memory is not passive. To remember is to choose what kind of history we value, and whose lives we consider worthy of attention. Writing about Heera Devi Yami is therefore not only an act of documentation, but an ethical act—an insistence that women’s labor under repression belongs to the historical record.

Her legacy lives not in monuments, but in continuities: in children educated against odds, in values passed on through example, in resilience normalized as daily practice. These are legacies that resist closure. They continue to shape lives long after political moments have passed.

This epilogue does not conclude her story. It acknowledges that her life exceeds the boundaries of this book. What it offers instead is an invitation—to listen more carefully, to look beyond official narratives, and to recognize history in places we have been taught not to search.

In honoring Heera Devi Yami through oral history, we affirm a broader truth: that history is sustained not only by those who lead from the front, but by those who endure, nurture, and hold communities together when visibility is dangerous and survival itself is an act of courage.