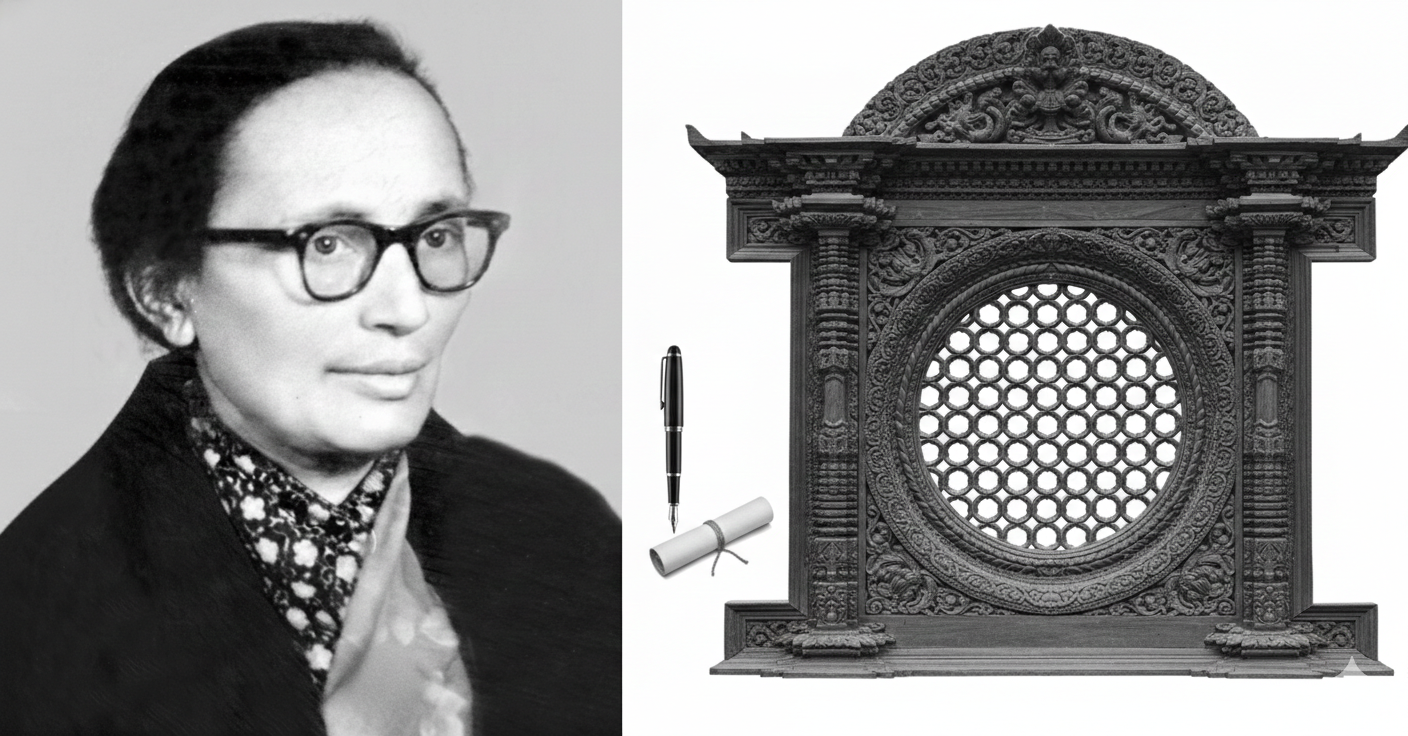

Discussions about AI and gender often begin in the present—about algorithms, bias, representation, and future jobs. But for me, this conversation begins much earlier, in a deeply conservative society, inside a household where a woman facing death made a radical decision about her daughters’ futures.

As my mother’s (Heera Devi Yami) health deteriorated, relatives from both sides of the family exerted intense pressure to marry off her atleast three daughters before she died. A health assistant repeatedly reminded her that her days were numbered. The fear among relatives was familiar and revealing: unmarried daughters, they believed, would be vulnerable after her death—morally, socially, and economically. Marriage was framed as protection; autonomy was framed as risk.

My mother understood that logic—and rejected it.

In our Newar society, early marriage for girls was not just common; it was expected. But my mother saw early marriage as a mechanism that locked women into inherited hierarchies and removed them from the future as decision-makers. She believed that once absorbed into those structures, her daughters would lose the ability to question, innovate, or transform society. To her, this was not only a gender issue; it was a development issue.

My father Dharma Ratna Yami was deeply engaged in political struggle, writing, and intellectual work. He did not manage household affairs. My mother carried the full burden of domestic life—raising seven children, managing finances, and ensuring that he was free to pursue public work. This was not passive sacrifice. It was strategic labor, undertaken with a long view of social change. She understood that invisible care work often underwrites visible political action.

Even as illness weakened her body, she remained adamant about one thing: her daughters would not be married off early. Instead, she insisted that all seven us enter science and technology. This insistence came in the 1960s and early 1970s—a time when even boys often chose arts and commerce streams, and when STEM was widely considered unsuitable, unnecessary, or even dangerous for girls.

My mother died in 1970 when she was only forty-nine years old, leaving behind seven children. We were young and vulnerable, suddenly without her protection, in a society that had never approved of how she ran our household or of the radical practices she insisted on. It would have been easy—almost expected—for us to retreat quietly into conventional ways of living. No one would have blamed us for doing so.

But she had already prepared few elder children. Through the way she lived, the way she explained her choices, and the absolute certainty with which she rejected caste hierarchy, she tried to shape the minds of understanding of integrity. She did not merely practice equality; she taught the society that there was no ethical alternative. Those values became part of who we were, not as an obligation, but as a way of seeing the world.

Her elder children partially understood this and, in turn, carried the younger ones with us—not through pressure, but through example. What she left behind was not property or security, but something far more enduring: a moral inheritance.

So we continued as she had lived. The doors of the house remained open. The kitchen stayed a place where caste was neither asked nor observed. Even as we navigated grief, uncertainty, and vulnerability, we chose continuity over retreat.

I now understand that this was her greatest achievement—not only that she lived her principles with courage, but that she ensured they would outlive her.

This is where her story intersects powerfully with today’s debates on AI and gender.

In the early 1940s, while battling tuberculosis in Calcutta, she found herself at the epicenter of a shifting world. As she struggled for her own breath, she read newspaper about the independence movement of Mahatma Gandhi.

Despite the physical toll of her illness, my mother remained a voracious reader, teaching herself to decode the complex geopolitical landscape of the era. Immersed in the chaos of colonial India, she reached a conclusion decades ahead of its time: if Nepal was to break free from the Rana regime.

She looked toward the educational corridors of Calcutta and Kalimpong. Her stay in Kalimpong and Calcutta made her realize that for a society to be truly stable and free from the hierarchies of the past, it needed the objective, empowering force of scientific knowledge. Her dedication was so profound that even today, surviving teachers from Amrit Science College (established in 1956 as PUSCOL) recall her visiting the campus to enquire deeply about the progress of science education. She didn't just want her own seven children to be educated; she envisioned an entire community technically equipped to solve the problems of a developing nation.

Today, artificial intelligence sits at the center of those systems.

AI is not neutral. It reflects the values, assumptions, and blind spots of those who design it. When women—especially women from historically marginalized communities—are excluded from science and technology, AI systems risk reinforcing old hierarchies under the guise of innovation. Bias in data, exclusion in design, and inequality in access are not technical failures alone; they are failures of human resource development.

Looking back, I now see my mother’s insistence on STEM as an early, intuitive response to a future she could not name but clearly sensed. She understood that power would increasingly flow through knowledge systems, technologies, and expertise. She wanted her daughters to be producers of that future, not its passive subjects.

In this sense, her resistance did not end with opposing early marriage. It extended into a vision of gender-inclusive capacity building, long before terms like “AI ethics” or “inclusive innovation” entered public discourse. Her life reminds us that conversations about AI and gender are not only about fixing algorithms today, but about decades-long investments in who is educated, who is trusted with complexity, and who is allowed to imagine the future.

If AI is to serve as a tool for social transformation rather than control, it must be shaped by diverse human intelligence. That requires recognizing women not as beneficiaries of technology, but as its architects.

This, ultimately, is my mother’s legacy: a reminder that gender justice in AI begins not in code, but in courage—often exercised quietly, long before the world knows what is coming.

I also remember my mother advising not only her own children, but the children of her friends. Whenever she spoke to them about their future, she urged them to enter the science stream. She would explain that science builds discipline, rational thinking, and the ability to solve problems—qualities a country like Nepal desperately needs.

At the same time, she never treated science as an escape from public life. She repeatedly told them that politics matters deeply in a country as vulnerable to political instability as Nepal. She believed that staying away from politics only left power in the hands of those least prepared to use it responsibly. For her, scientific training without political engagement was incomplete.

She encouraged young people to stay connected to political life, to enter political struggles consciously, and to be ready to face hardship and opposition. She knew political participation in Nepal was neither safe nor comfortable, but she believed that meaningful national development required people who combined technical knowledge with political courage.

Looking back, I see this as a remarkably advanced understanding of human resource development. My mother was arguing—without using the language we use today—that a nation cannot develop through technology alone, and that politics without scientific thinking is equally dangerous. She envisioned citizens who could think scientifically, act ethically, and engage politically.

In today’s context of artificial intelligence, her advice feels strikingly relevant. AI shapes governance, labor, and social systems, especially in politically fragile environments. Without people trained in science who are also willing to engage politically, AI risks becoming another instrument of inequality or control. My mother’s insistence on science paired with political participation anticipated the very challenges we now face.

Her words remain with me as a guiding principle: build technical competence, but never abandon the political battle. For her, this was not a contradiction—it was the foundation of responsible nation-building.

In the era of artificial intelligence, I increasingly see how my mother’s thinking and the advice she left behind are deeply relevant to human resource development. She believed that scientific education must be paired with political awareness, ethical responsibility, and the courage to engage with social instability—especially in a country like Nepal. Today, as AI reshapes labor, governance, and decision-making, her insistence on building technically skilled yet politically conscious citizens feels prescient. What she understood intuitively is now clear: without people trained to think scientifically and act responsibly, advanced technologies risk reinforcing old inequalities rather than transforming society. In this way, her legacy continues—not only as memory, but as guidance for shaping human capacity in the age of artificial intelligence.